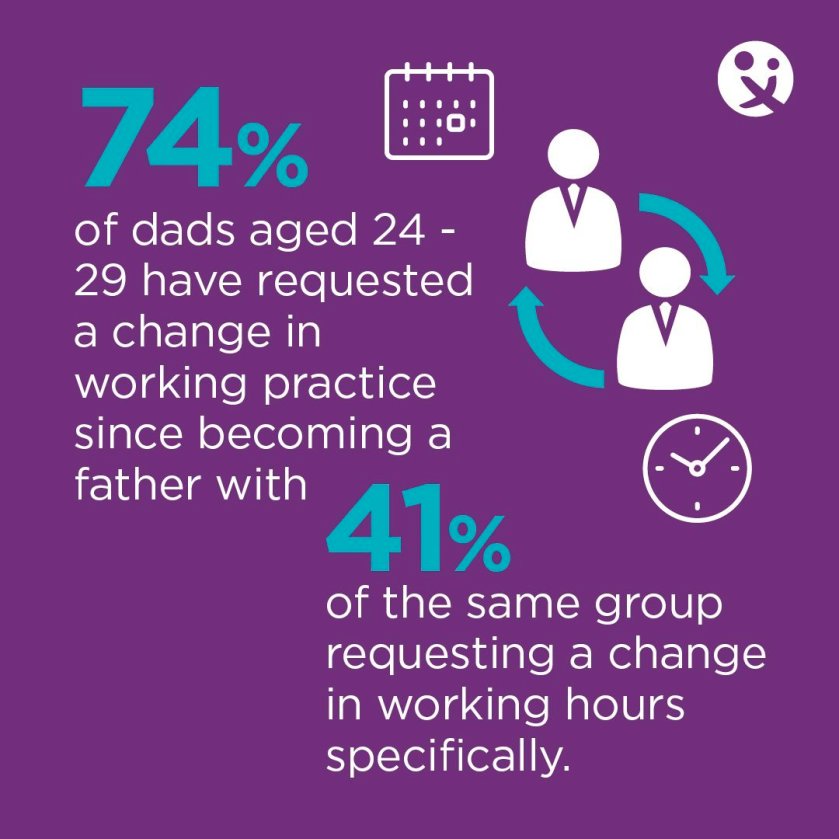

The role of the working mum is well-established; however in recent years we have seen the rise of the working dad. Increasingly, dads are making more requests for flexible working arrangements than ever before. In fact, a recent study by daddilife.com, produced in association with Deloitte, found that nearly two thirds (63%) of dads have requested a change in working pattern since becoming a father.

According to the study, modern day fathers are more involved in parenting than ever before. In fact, the study claims 87% of the dads surveyed are either mostly or fully involved in day to day parenting duties. So much so that dads are increasingly putting fatherhood ahead of their careers, or at least accepting the need for a better balance between work and home life after the birth of a child.

Requests for flexible working patterns might include asking to spend a day or two working from home every week. Perhaps so they’re present for the nursery run, or for half an hour of play and interaction at lunchtime. Likewise, the need for flexible working could be for compressed or reduced hours, so new dads can spend more time with their children during those crucial early years. Whatever it is, new dads are asking for more flexible working in record numbers. This is because, more than ever, they value time spent with their young families.

The study suggests that millennial dads are prepared to take drastic action to make sure they achieve a lifestyle that is good for work and good for their families. The research found that a third of dads had already changed jobs since becoming a father. In addition to that a further third were actively looking to change jobs. That’s an interesting finding as far as employers are concerned. It shows that offering flexible working for parents (both mums and dads) is likely to help them retain their top talent.

The study also suggests that, at the moment, too many organisations are letting good workers drift into the arms of other organisations. Specifically, the ones who are more sympathetic to the need for better flexibility at work.

The worry is that not all employers are getting the message. For instance, the Deloitte research reveals that, while 14% of dads have requested to work from home on one or two days a week, less than one in five (19%) have had the request granted. Similarly, 40% of the dads interviewed have requested a change in working hours but nearly half of them (44%) have been turned down.

Dads are increasingly reporting that the greatest life satisfaction comes from being an involved and present parent. Too often though, they bump up against a workplace environment that is sadly out of touch with that sentiment.

Nearly half (45%) of working fathers regularly experience tension from their employer when trying to balance work and family life, while 37% regularly experience tension from colleagues, and 45% with their partners.

Society may be gradually more accepting of the fundamental role that fathers play in creating happy, well-adjusted children, but many workplaces are lagging behind. As a result, dads are suffering because of that, and organisations are too. Unhappy workers are never at their most productive. As we’ve seen, businesses who fail to offer better work/life balance for parents risk losing top talent to more enlightened competitors.

Thanks to Hugh Wilson at daddilife.com for his excellent insight and commentary on the Millennial Dad at Work Report, which I have summarised here, to check out Hugh’s full article, click here. Hopefully reports such as this will lead to greater understanding and increased flexibility for working dads.

You can also check out the full published report by daddilife.com, in association with Deloitte, by clicking here.

JD